The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was the most perilous event in history, when mankind faced a looming nuclear collision between the United States and Soviet Union. During those weeks, the world gazed into the abyss of potential annihilation.

One of its most terrifying moments came on 18 October, when President John F. Kennedy and his advisers discussed the prospect that, if US forces invaded Cuba to remove the missiles secretly deployed there, the Soviets would seize West Berlin. Robert Kennedy asked: Then what do we do?. General Maxwell Taylor, chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, said: Go to general war, if its in the interests of ours. The President asked disbelievingly: You mean nuclear exchange?. Taylor shrugged: Guess you have to. His words highlight the madness that overtook some key players on both sides. Mercifully, JFK recoiled from the soldiers view saying: Now the question really is to what action we take which lessens the chances of a nuclear exchange, which obviously is the final failure.

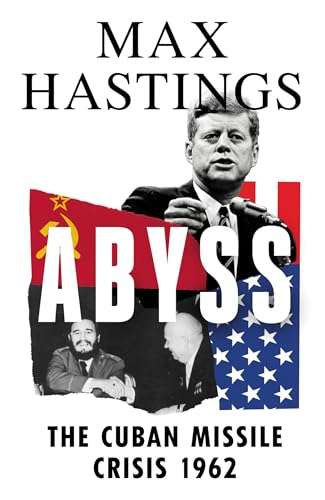

Max Hastingss graphic and brilliant new history tells the story from the viewpoints of national leaders, Russian officers, Cuban peasants, American pilots and British disarmers. Max Hastings deploys his accustomed blend of eye-witness interviews, archive documents and diaries, White House tape recordings, top-down analysis, first to paint word-portraits of the Cold War experiences of Fidel Castros Cuba, Nikita Khrushchevs Russia and Kennedys America; then to describe the nail-biting Thirteen Days in which Armageddon beckoned.

Hastings began researching this book believing that he was exploring a past event from twentieth century history. He is as shocked as are millions of us around the world, to discover that the rape of Ukraine gives this narrative a hitherto unimaginable twenty-first century immediacy. We may be witnessing the onset of a new Cold War between nuclear-armed superpowers. To contend with todays threat, which Hastings fears will prove enduring, it is critical to understand how, sixty years ago, the world survived its last glimpse into the abyss. Only by fearing the worst, he argues, can our leaders hope to secure the survival of the planet.

In Khrushchevs memoirs, he asserted that the notion of the Cuban deployment [of nuclear weapons] first came to him during a May visit to Bulgaria: Something had to be done to make Cuba safe. But what? The idea gradually took shape in my mind. I didnt tell anyone what I was thinking. This was my personal opinion, my inner torment. Yet it is generally accepted that he had already mooted the plan while staying at his Black Sea dacha, the very place where he so often peered across the limpid waters through binoculars and inveighed against the American Jupiter missiles sited in neighbouring Turkey. A month earlier when defence minister Marshal Rodion Malinovsky arrived to brief his leader on the latest state of the nuclear balance, as a preliminary to demanding more resources, the chairman had suddenly demanded: Rodion Yakovlevich, what if we throw a hedgehog down Uncle Sams pants? He had conceived a grandstand play: to make a covert deployment to Cuba, then stun the world with an announcement of it, at his planned UN General Assembly appearance in November, after the US mid-term congressional elections