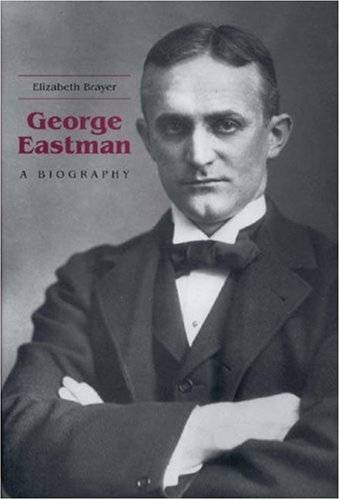

The innovative founder of the Eastman Kodak Company was not generally known for his thirst for adventure, his love of art and classical music, or his philanthropic activities, yet these were all important aspects of the man. George Eastman (1854-1932) was a complicated individual who lived most of his long, industrious life out of the public eye; his private affairs both admirable and dubious are now out in the open, thanks to this scholarly and scrupulous biography. Eastman is revealed as cold, shrewd, modest, and surprisingly generous in this colorful portrait. The text is appropriately enhanced by a number of rare photographs.

--This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

From Publishers Weekly

In 1904, when the Dalai Lama had to flee Tibet, he took his Kodak camera. Worldwide, people understood. The cultural revolution begun in 1888 when George Eastman (1854-1932) made photography accessible to anyone with $25 had been completed in 1900, when his Brownie made picture-taking possible for anyone with a dollar (and 15? for film). Brayer, a historian at the Eastman-endowed International Museum of Photography and Film, has written a candid, fact-crammed life of the first camera-and-film tycoon that loses somewhat in liveliness by leaving out almost nothing about how the camera business was dominated for years by Eastman's canny and baronial practices. A bank clerk as a young man, he was astute enough by his late 20s to weather financial difficulties and manufacture cheap, workable film while withstanding what would become decades of litigation, much of which he won, over patent infringement and antitrust charges. In the end the mother's boy who could never cut the silver cord and marry was wedded to an enterprise that made him, in wealth, a peer of Rockefeller, Carnegie and Ford. Catchphrases advertising his cameras ("You Press the Button, We Do the Rest") sold billions of feet of film and threatened to make "Kodak" a common noun for "camera." He resisted with challenges over trademark and with the maxim "If it isn't an Eastman it isn't a Kodak." His relentless social Darwinism would pay off in consolidations, mergers and buyouts that left him with so many dollars (and no heirs) that only massive educational and cultural philanthropies could reduce the accumulation. "Mr. Eastman," one associate concluded, "was the only man I ever knew who started out a conservative and wound up a liberal." Brayer's biography of the boy fired up by "Oliver Optic" stories such as Work and Win and A Millionaire at Sixteen captures the expansive if callous period in American business in which such fortunes were made.