Published by Penguin Classics, 1969, softcover, 301 pages, condition: very good.

Of the three plays in this volume, Ghosts and A Public Enemy are social dramas of his middle period; and the former, described by one London critic as "an open sewer," raised the greatest outcry of all Ibsen's attacks on convention. When We Dead Wake, his last play, handles in a symbolic manner the individual's inner conflict and, incidentally, provides the dramatist's own comment on his lifework and his renunciation of work.

Recently, I had an overnight in Oslo, and my husband suggested we visit the Ibsen Museum. There I bought this edition of three of Ibsen's plays, which I loved. I also loved the foreward by translator Peter Watts, and I think he deserves a lot of credit for how utterly contemporary the plays feel. He notes that Ibsen expected his plays to be read like books, and you really can do that, given the detailed stage and set directions.

In "Ghosts," a strong woman has kept the secret of her husband's dissipations from her son but realizes too late that the "ghost" of the dead father is appearing in the young man. Ibsen plays around with different ways of seeing in this play, addressing the relationship between physical sight and insight.

I loved the doctor protagonist in "Enemy of the People," and was not surprised to read in the newspaper that the play is now being produced as a comment on the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. It is right on point. The doctor sticks with the dictates of conscience and tells the truth about a polluted water supply despite consequences to his family's economic future. He can't even be said to wrestle with the problem. Other people do, but he remains clear-eyed and idealistic throughout. But for me, "When We Dead Wake" was the most riveting, with its attention to the competing tugs of artistic expression and the art of living a life. At first, I was reminded of the Sondheim musical "A Sunday in the Park with George" Seurat, a pointillist painter who is imagined putting art above his relationship. But that play justifies the artist's choices as necessary, whereas Ibsen toward the end of his life clearly had profound regrets about some of his past priorities.

The back and forth between sculptor Rubeck and the model who inspired him (and then disappeared because she realized she was only "an episode" to him) was fascinating to me. I felt that "art" in this play could stand in for many other kinds of pursuits that we think are important in life, until we realize we should have devoted more energy to love or family or other goods.

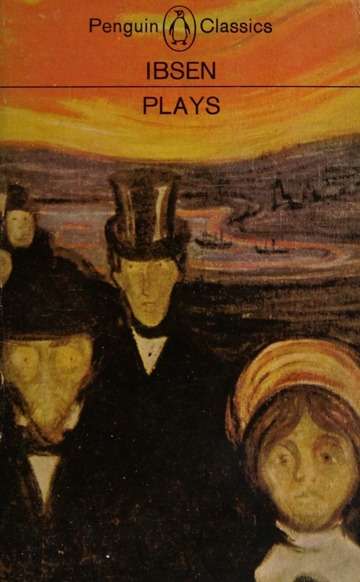

I also love that editions of Ibsen (and other Norwegian authors) use the art of fellow mournful Norwegian Edvard Munch for their covers. So appropriate!