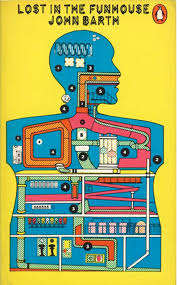

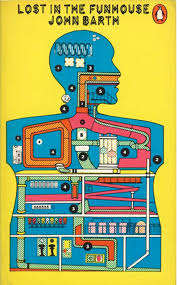

Lost in the Funhouse

Check my rate

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

Penguin, 1972, softcover, 198 pages, condition: very good.

John Barths titular short story, Lost in the Funhouse, from his subversive short-story collection Lost in the Funhouse, is an overt example of the theories discussed .. In terms of story, Lost in the Funhouse is a rather simple tale that deals with a family trip to an amusement park and specifically, the funhouse. The main protagonist is 13 year old Ambrose who gets lost in the funhouse any discerning reader would not have to work hard to see how a story of a pubescent teenage boy in the company of an uninterested teenage girl could find himself, both literally and metaphorically, lost in the funhouse. However, considered alongside the theories I have discussed on this website, another layer of interpretative reading materialises that, I believe, secures Barths postmodern presence within a much wider contextual standing.

"He wishes he had never entered the funhouse. But he has. Then he wishes he were dead. But hes not. Therefore he will construct funhouses for others and be their secret operator

Often touted as the definitive metafictional text, Barths Lost in the Funhouse explicitly explores the authors self-referential placement within the text, the author not only becomes a character in the story but additionally, this narrative device also adds another interesting tier to the story, it becomes a fragmented written feature about writing which aligns itself entirely with Linda Hutcheons beneficial definition of metafiction; fiction about fiction-that is, fiction that includes within itself a commentary on its own narrative and/or linguistic identity. (Hutcheon, 1980, p.1) the authors seeming loss of control over the text is mirrored by our protagonists own lack of authority and control - as he stands in the mirror-room unable to acknowledge himself from another perspective other than the one that is presented in front of him In the funhouse mirror-room you can't see yourself go on forever, because no matter how you stand, your head gets in the way (Barth, 1988, p. 85). This introspective vision of Ambrose attempting to see himself is somewhat rather indicative of the entire postmodern manifesto (not that such a helpful thing exists); any attempt at trying to be too far removed from yourself (or your work) will only frustrate you - the exact sentiment Barth was trying to convey in his essay when he said that the all-too-often imitation of the same novel format that is reproduced over and over was desultory and that only looking forward (to new authorial styles) will result in original works. In a metaphorical mirror-room, the reader is presented with the same old familiar vision, an arbitrary intermediary that the author and reader fruitlessly partake in.