The 1st April 1989 marked the first day of peace in Namibia. After seemingly endless years of dispute between South Africa and the United Nations, after 23 years of bush warfare between the Marxist orientated South West Africa Peoples Organisation SWAPO, and South African forces, which had spread from Namibia into Angola and, at times, into Zambia, and after eight months of American brokered talks between South Africa, Cuba and Angola, Namibia was finally on course for UN supervised free and fair elections in November 1989, which would lead to independence in 1990. The South Africans had stuck strictly to the letter of the agreements and even more.

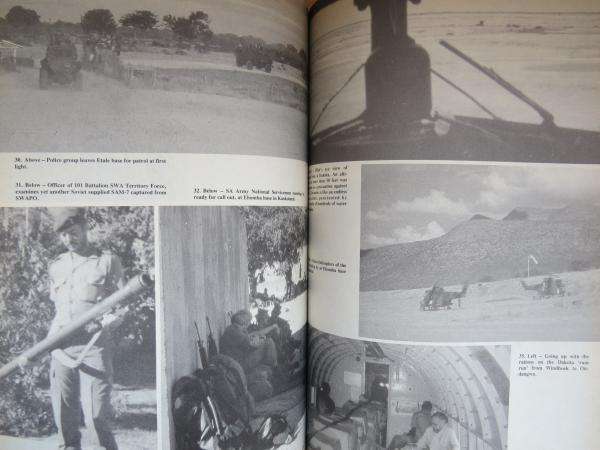

By the 1st April they had demobilised the powerful SWA Territory Force, drastically reduced the strength of the SADF and confined the residue still remaining in Namibia to bases. When the sun rose on that fateful day, it would catch the shadows of only five SAAF Alouette helicopter gunships, emasculated of their deadly cannons, and dispersed along 400 kilometres of Namibian border with Angola. SWAPOs leader, Sam Nujoma, knew it, for the knowledge was international property via the UN.

Nujoma had transmitted his written agreement to a ceasefire to the UN Secretary General in late March. But while smilingly professing he was for peace, he was behind the scenes preparing for war. More than 1 600 of his PLAN fighters, who should have long been removed to camps north of the 16th parallel by the Angolan and Cubans under UN supervision, were massing in Angola along the Namibian border, heavily armed with everything from anti tank to sophisticated anti aircraft weapons. On the night of the 31st March1st April, they surged over in what they obviously believed was an unstoppable wave. A wave which once it broke into pools, they believed, would be allowed by a weak UN to remain in Namibia and subvert the elections by means of a brutal intimidation campaign.

But they overlooked a wild card. It was a thin blue line of some 1 200 SWA policemen of the northern border command, many of them former members of the counter-insurgency unit, Koevoet, whose heavy weapons had been removed from their Casspirs in terms of the peace plan. But what those policemen, mostly black with a sprinkling of white commanders, lacked in weaponry, they more than made up for with sheer guts, fighting skills and undying courage.

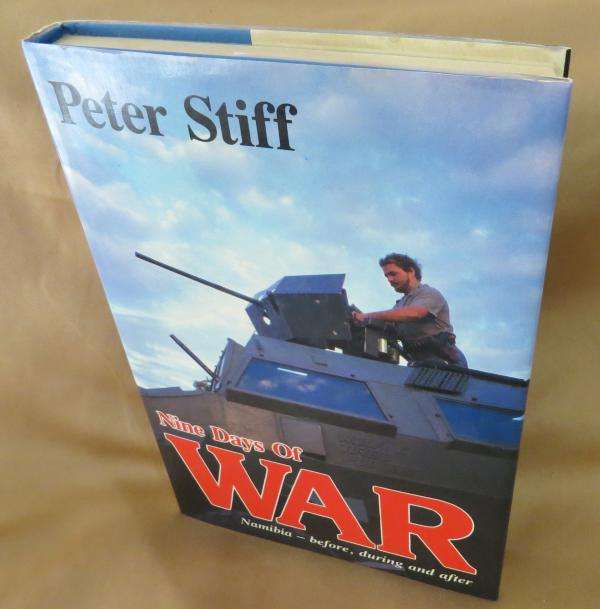

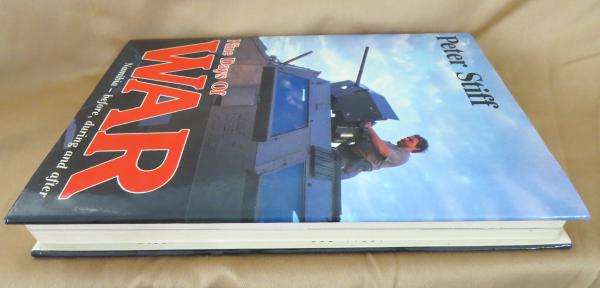

For nine bitter days until the Mount Etjo Agreement was signed, they fought the SWAPO infiltrators to a grim standstill, in the closing stages with air force and military help, beating them hands down. Peter Stiff was there while the fighting was on. He spoke to Administrator General Louis Pienaar and people in his administration, Gen Prem Chand and men of his UN command, South African diplomat Derek Auret, SADF Chief Gen Geldenhuys, SWA Police Commissioner Gen Dolf Gouws, Regional Commissioner for the northern border, Gen Hans Dreyer and many other senior military, police and civilians as well.

But above all he spoke to the policemen, airmen, soldiers, medics and even captured SWAPO fighters in the field, often when they were fresh from battle, from whose stories he has written this unmatched almost blow by blow account of the fighting. It is all here. It is Peter Stiffs story, without any form of censorship or restriction, of Namibia before it happened, while it was happening and what has happened since. It is an amazing and thought provoking account, impossible to ignore.