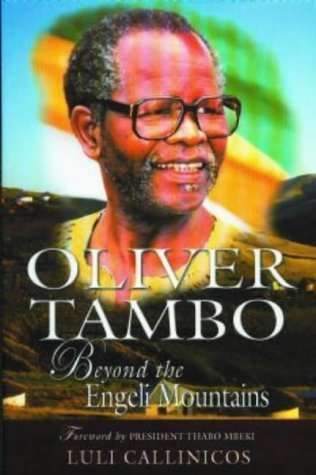

Oliver Tambo: Beyond the Engeli Mountains by Luli Callinicos

Check my rate

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

Published by David Philip, 2004, illustrated, index, 672 pages, condition: as new.

Oliver Tambo is deserving of a biography. He is the man who held the African National Congress (ANC) together throughout all the years of exile, when Nelson Mandela was in prison. He is the man who ensured that there was an organisation in place for Nelson Mandela to lead when he was released from prison. He is the man who nurtured and encouraged the resistance to apartheid both in South Africa and throughout the world from 1962 to 1990. He is the man who encouraged generation upon generation to believe that we could win, when the world told us we were wasting our time. He is certainly deserving of a biography. This one is not new. It was first published in 2004, to coincide with the tenth anniversary of freedom in South Africa. One of the questions that I have to ask myself therefore is this: Why has it taken me so long to read this book? Part of the reason is that the book was quite difficult to get hold of in this country. But that is an excuse. I worried that I had been too close to the events, and I had only really been on the periphery, and that it would be difficult to make an objective judgement. It is now 25 years since Oliver Tambo died, and I think that I am in a position to make that judgement.

I should explain. I was chair of the London Anti-Apartheid Committee in the 1980s. I met Oliver Tambo on a few occasions. It would be untrue to say that I was acquainted with him, although I spoke to him directly on occasion and I think that he was aware of who I was. I was certainly known to his wife, Adelaide, and to his children, Thembi, Dali and Tselane. I played with his grandchildren, Thembis boys, Sasha and Oliver on occasion. I was a volunteer at the ANC Office in 28 Penton Street and at the Department of Information and Publicity Office in Mackenzie Road. This latter was a secret office, and you really had to be trusted to be allowed to work there. I attended the ANC International Solidarity Conferences at Arusha in Tanzania in 1987, and in Johannesburg in 1993. I worked as a volunteer in the ANC Office in Jeppe Street, Johannesburg, during the 1994 election. I cannot claim that I was neutral, and this is why I was worried about reading this book. Of course, I did not need to worry. Oliver Tambo may have been a self-effacing man and certainly not self-promoting, but he had an acuity of mind that made his judgement good. If Oliver Tambo thought that Luli Callinicos was a suitable person to write his biography that is simply because she was. It is a task that she takes on with sensitivity and understanding, recognising his merits and dealing with the difficulties that arose, of which there were many. Callinicos begins with his upbringing in the village of Kantolo, district of Bizana, in Pondoland on the far east of the then Cape Province (now the Eastern Cape). Tambo was born into a traditional Mpondo family. His father had a number of wives, and children by all of them. Oliver had his mother and his other mothers. The community lived by farming, until the introduction of the Poll Tax which necessitated the men to go away to earn money in order to pay the tax. This was disruptive and some of the men were injured or, in the case of one of Olivers uncles, killed because of the unsafe conditions in the mines. Olivers father was determined that his son would be educated so that this would not happen to him, and so his son was sent away to missionary schools. By then, he had already learned the tradition of African leadership, of listening to a discussion, of summarising it at the end and of leading people to a decision. This tradition of ubuntu after an indaba was something that he was to practice throughout the whole of his political career. The other major factor about Tambos character was his deep commitment to Christianity and specifically to the Anglican Church. This partly came about through the education that he received at St. Peters school, a Community of the Resurrection school, in Johannesburg. It is also partly because of his enduring friendship with Trevor Huddleston, a member of the Community, and a deeply passionate campaigner against apartheid. It was mainly, however, because of his deep spirituality and the strength that he gained from this belief, which helped him to lead the ANC through all the difficult years of exile.

What we have is a remarkable story about a remarkable man. He was patient and kind. He was not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. He never insisted on his own way. He was not irritable or resentful. He did not rejoice in wrongdoing, but in the truth. He bore all things, he hoped for all things, he endured all things. Oliver Tambo made a significant and indelible contribution to the liberation of his country. He was one of the great leaders of the twentieth century.