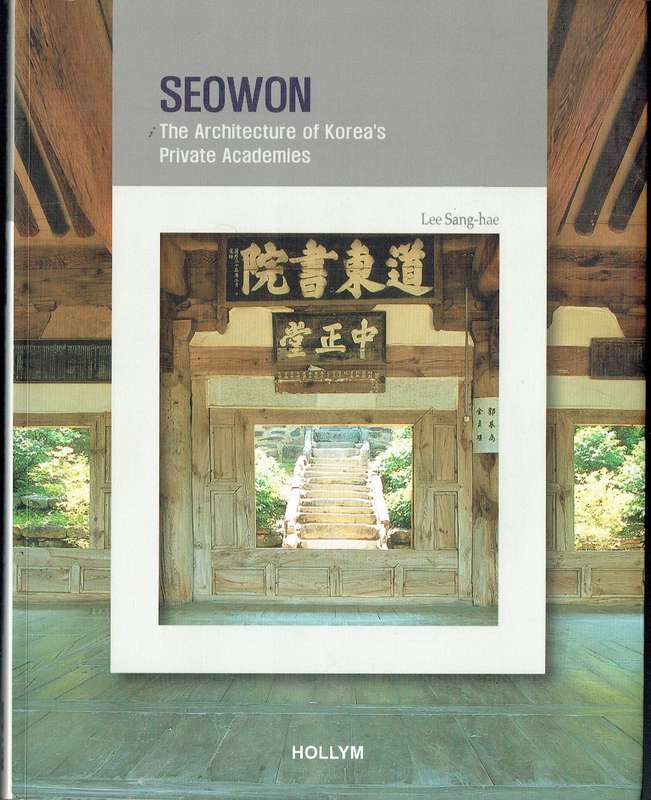

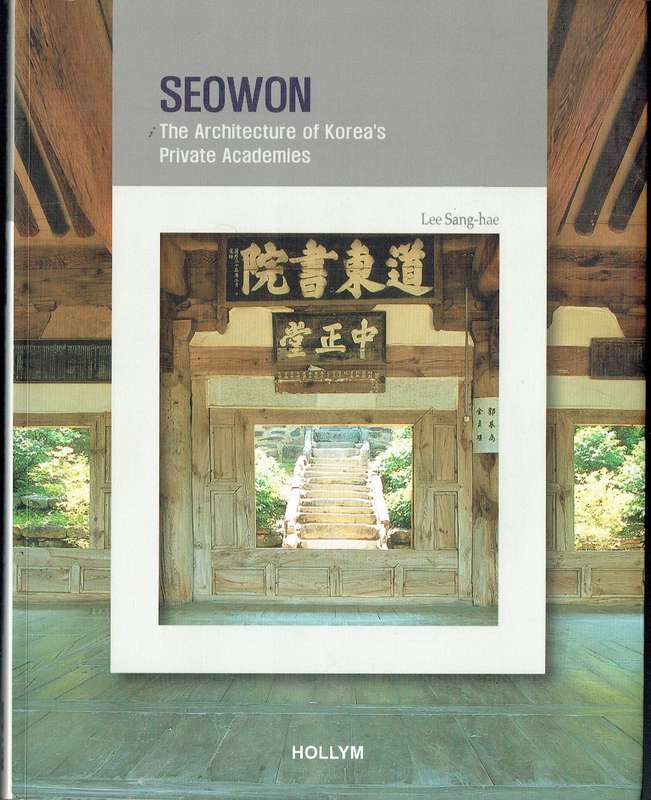

Seowon: The Architecture of Korea's Private Academies

Check my rate

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

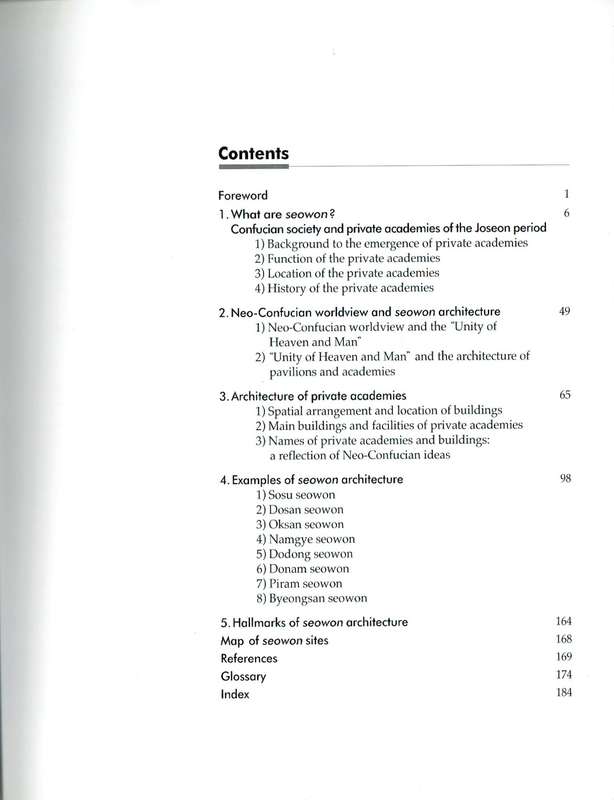

Lee Sang-hae, Seowon: The Architecture of Korea's Private Academies. Elizabeth, New Jersey: Hollym, 2005.

Large soft cover, card wraps, 201 pages, well illustrated.

In 'as-new' condition.

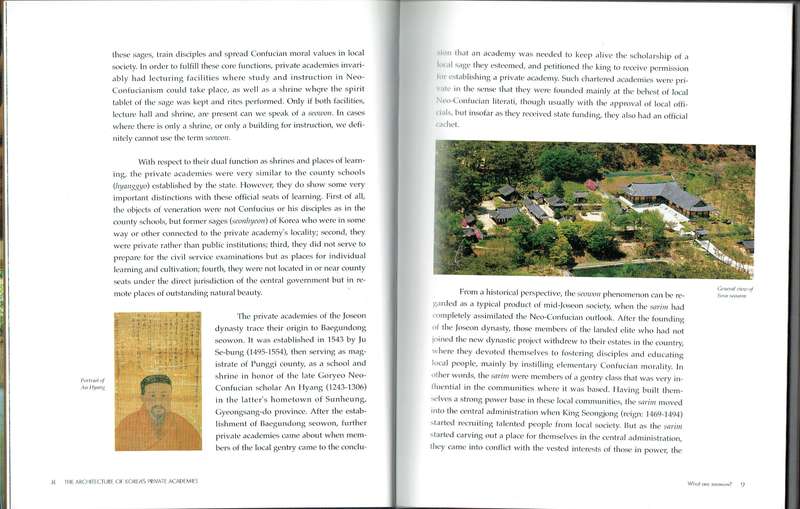

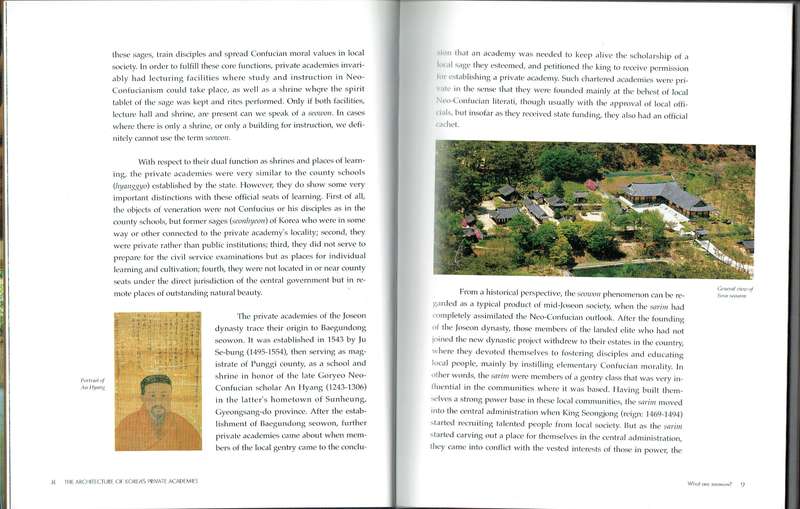

'Seowon (private academies) are the crowning glory of Korean Neo-Confucianism, a cultural tradition originating in China but absorbed by Korean literati of the Joseon period and adopted as their ruling ideology. These literati, known as sarim, built seowon near murmuring brooks and imposing mountains, as retreats where they could steep their minds and bodies in the study and practice of Confucianism, and keep alive the tradition of previous Korean sages by enshrining them as objects of worship.

Amidst the seowon buildings, the sarim students and scholars could enjoy the cool breeze and moonlight while discussing their study without any constraints, but these buildings also served as schools to study the mandate of Heaven and the order of nature. The seowon was the place where the literati came to explore the origin and destiny of all things, and to understand the relationship between human nature and the principle of Heaven. Here they were inculcated with the notion that by constantly renewing one's own heart and mind, not only society but all other things could be reformed as well. They were not just academies of learning; instead of merely picking up knowledge, the students would absorb this knowledge as a catalyst for beauty and goodness, so that they could work to achieve goodness in themselves and in society. The seowon educational system imbibed them with a strong sense of jus-tice and trained their spirits so that as officials they would not yield to injustice but face an honorable death or exile rather than relinquish their integrity.

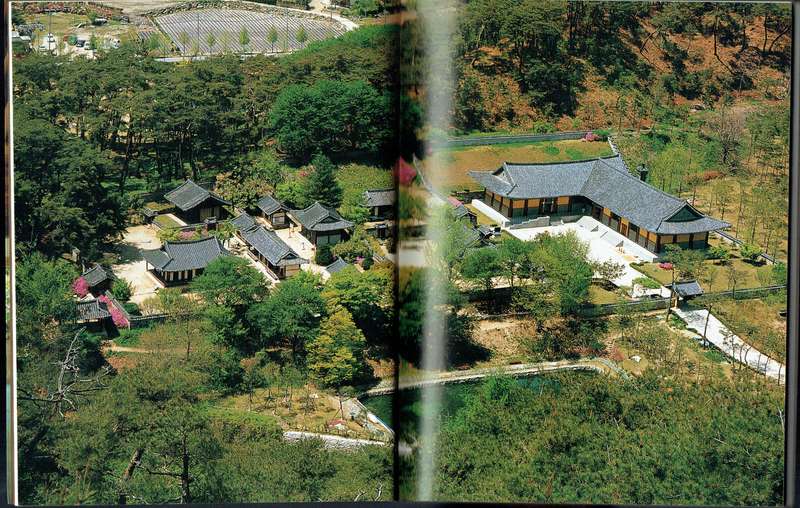

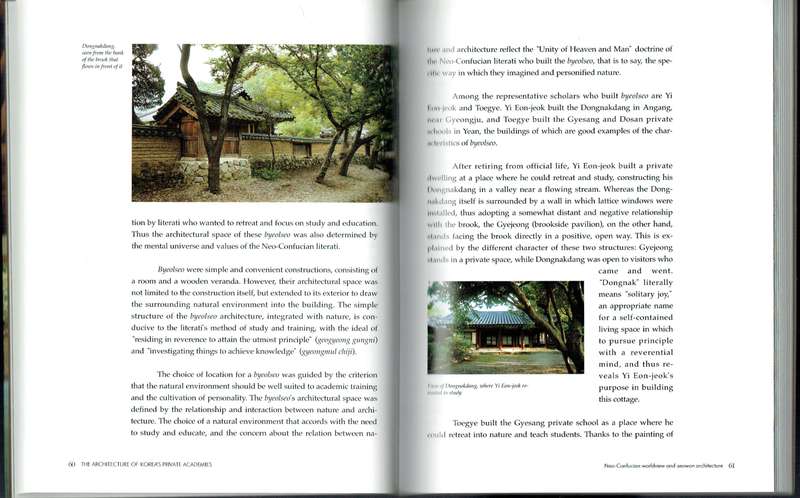

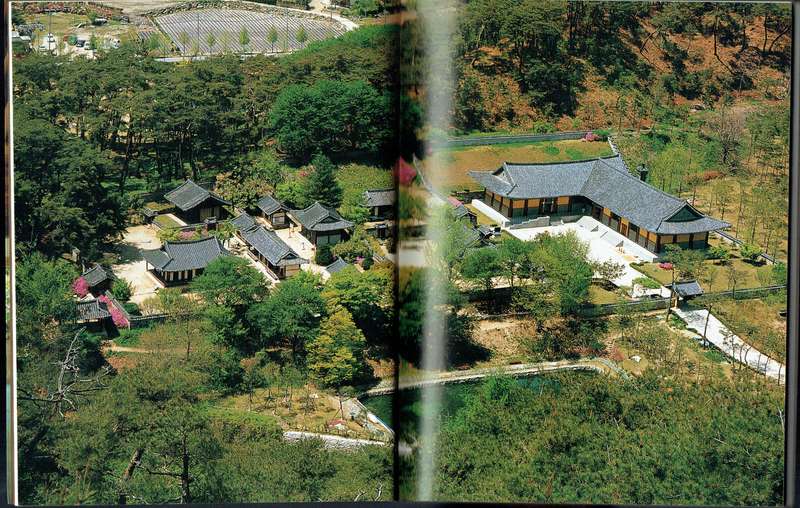

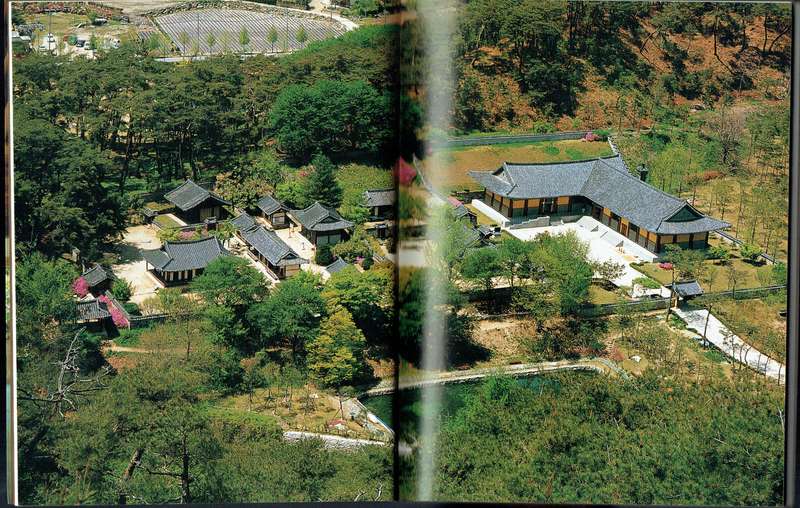

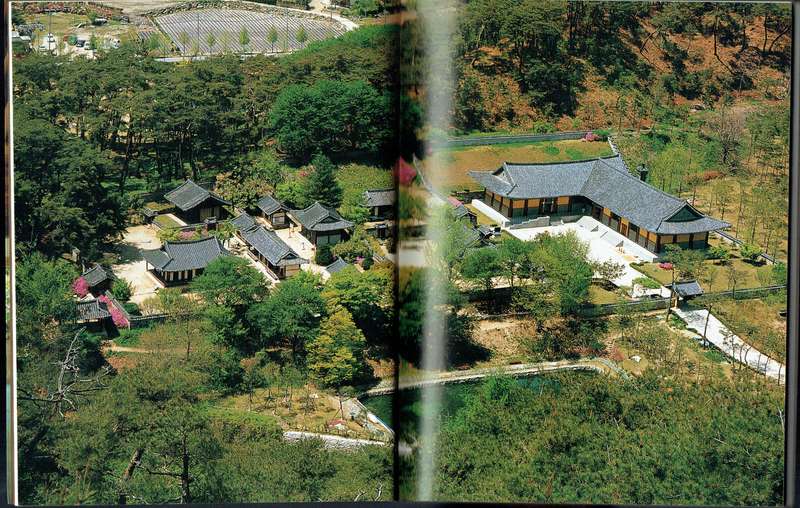

In this sense the seowon express the mental universe and views on nature of the Joseon scholar-officials, but they also show how architecture can transform the surrounding landscape through an aesthetic of space and serve as important examples of traditional Korean architecture.

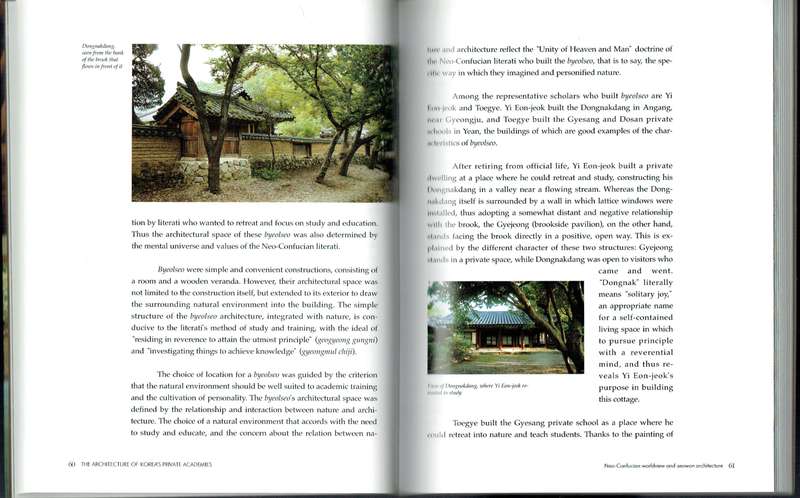

Most seowon are wonderful architectural spaces that are completely in tune with nature, that interpret and reinterpret the landscape surrounding them and are actually completely at one with the landscape. They have become an integral part of the natural environment, while this environment has also became part of the seowon, or at least one of its important features. This shows that architecture was conceived in relation to its emplacement, its environment.

Moreover, the simple, moderate life pursued by the sarim literati and their views on nature are well reflected by the seowon architecture. The simple and elegant building style, the management of the architectural space and the layout of the buildings, which are clearly ruled by an intention to embrace the surrounding natural environment and make it part of the Neo-Confucian conceptual universe, all testify to the sarim's pursuit of a Neo-Confucian ideal. These architectural characteristics are based on a restrained and abstract sense of aesthetics, which is fundamentally different from the popular aspects and decorative exuberance of Buddhist temples. In sum, the seowon is nothing other than the physical expression of Neo-Confucian values, worldviews, and understanding of nature.

Historically, Korea has always been exposed to the influence of Chinese culture, but at the same time it has also managed to retain its own, distinct culture. Because the topos, the natural environment, is different from China's, the character of the Korean sarim was also different from that of the Chinese literati. Seowon are a good example of this. Seowon architecture blends a building style that is suitable to the mountainous Korean peninsula with a Neo-Confucian worldview. The spiritual world of the society that produced them is projected onto the seowon, which construct a small universe in which to train the minds and bodies of scholars, provide a place to indulge in nature and celebrate life, provide a framework where student and teacher share the same way of life, and form a spiritual center to reform local society.

I have done my best to produce a book that introduces seowon architecture not just to foreign students and scholars of Korean culture, but also to anyone interested in Korean culture, and provides them with a profound understanding of it. Great care has been taken to match the text and the accompanying photographs so that those who want to understand traditional Korean culture and architecture can get the maximum benefit. I hope that by providing a genuine picture of the function and role of Korean seowon architecture, readers can obtain a fresh awareness of Korean culture.'