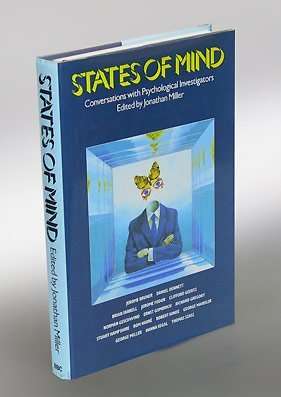

States of mind: Conversations with psychological investigators

Check my rate

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

| Main centres: | 1-3 business days |

| Regional areas: | 3-4 business days |

| Remote areas: | 3-5 business days |

Published by British Broadcasting Corp, 1983, hardcover, illustrated, 312 pages, index, 16,2 cms x 23.6 cms, condition: as new

Jonathan Miller's book, States of Mind, is based on a television series shown on BBC.. The book is a very well edited transcription of fifteen interviews with psychologists, anthropologists, and sociologists, including such notables as George Miller, Jerome Bruner, and Rom Harré. The contributors probably familiar to most AI researchers are Daniel Dennett and Jerome Fodor, as well as two contributors well-known for their writing on art and perception, Ernst Gombrich and Richard Gregory. The interviews are uniformly intelligent, original, and stimulating. As summaries of basic arguments about mental models, perception, and ethical questions of mental problems, you can't do better than this collection. Miller is especially good at explaining the motivations for traditional psychology and how it has evolved into its present-day cognitive form. The anthropologists and psychiatrists in particular are unrelenting humanists who provide convincing tutorials on how their fields have advanced, making previous work understandable without being condescending. Probably the most interesting thing to be discovered in this book is how the simple theme of constructive understanding plays a pivotal part in modern explanations of perception, language, problem solving, and interpersonal relations. By this perspective the specialists share a common methodology for analyzing processes and systems that we are all intricately part of. The clarifications by Harré and Geertz, for example, of how language places us apart from animals, are stunningly clear and valuablesomehow obvious, but again and again missed by the public mind.

A collection of this kind provides a valuable opportunity for AI researchers to develop their models of reasoning by constructing interfield analogies. The studies in States of Mind fall naturally into two categories: mental/perceptive and social/psychiatricmicro and macro perspectives on the nature of thought. While it is common to suppose that AI needn't be limited to mechanisms used by the brain, we more rarely consider the large-scale implications of placing an independent intelligent agent in an uncertain world, an agent with perhaps contrary goals, whose expectations are sometimes violated, and whose failures to understand the world lead to continuous striving for an overarching meaning. For mankind, this is the stuff of psychology, religion, and magic. Machines may be freed of the limitations of the human brain, but how will they cope with the existential problems of the universe? The overall scope of the book is quite broad; applying the ideas to AI requires some condensation and reinterpretation. Miller isn't writing for AI researchers, nor does he fully realize in his commentary the striking similarities of methods and results in the diverse fields. Therefore, to synthesize what the contributors are saying for an AI audience, I'm going to develop the main theme of constructive understanding in some detail. This idea is so powerful and importantone of the key insights of our centuryevery AI researcher should know it as well as theories of logic or search. To whet your appetite, the discussion will show how Harré's analysis of violence in football games is related to Gombrich's study of drawing (and why AI researchers should care). We begin with a brief consideration of the evolution of cognitive psychology and the study of the brain.

Miller tells us that, In its understandable effort to be regarded as one of the natural sciences, psychology paid the unnecessarily high price of setting aside any consideration of consciousness and purpose, in the belief that such concepts would plunge the subject back into a swamp of metaphysical idealism. (p. 32) In their interviews, George Miller and Bruner relate how theories of machines, such as servo-mechanisms and signal detection and information theory, reintroduced the idea of internal states, something represented in the machine about its world. In this way, the use of terms like goals and expectations became respectable again the kinds of things (engineers) say about machines, a psychologist should be able to say about a human being. (p. 23) I have simplified the arguments here for brevity. The interviews provide a readable, technical discussion that might be expected in any advanced text. The discussions by Gregory, Fodor, and Geschwind are full of fascinating examples. We are treated to a discussion of our inability to intellectually juggle an optical illusion, raising intriguing questions about the effects of biased expectation on higher problem solving. Fodor's discussion of a Wittgenstein thought experiment fairly demolishes the idea that a mental image could be just an internally generated and inspected copy of the world. (Form a picture of a man climbing a hill with a cane. How do you know what that's a picture of? Could it be a man sliding back down the hill, dragging his cane after him?) Geschwind tells us of the disunity of the mind, how in disturbed patients, the right half always seems to act aggressively towards the left. Again, these problems are all considered in substantial technical detail, made understandable, but not popularized. The specialists manage to enchant us with their recent findings: Brains, like hair color and height, differ from person to person; different internal systems, often at a distance from one another and under different kinds of control, can effect the same behavior, such as facial movement.