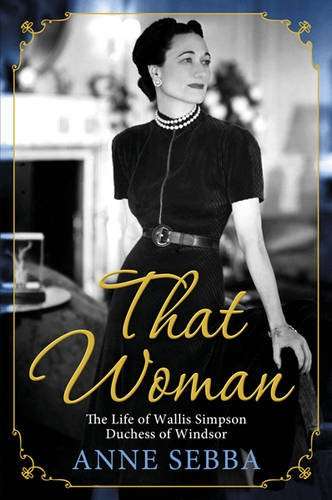

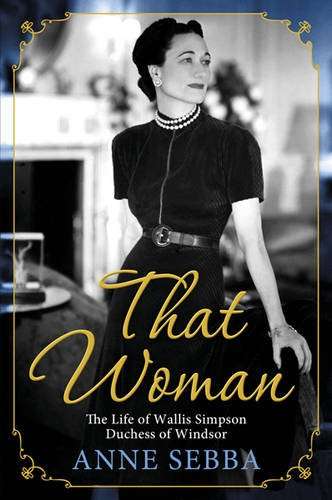

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2011, illustrated, index, 344 pages, condition: very good.

This serious yet sympathetic biography explains how American divorcee Wallis Simpson became a hated woman for allegedly ensnaring a British King from his throne. That Woman focuses on the core conflict of her life in the 1930s, and also references her impoverished childhood as a motivation for her ambition.

Wallis was called 'That Woman' by her sister-in-law the Queen Elizabeth. In death, Wallis has become one of the most written about and reviled women. But she has also become a symbol of female empowerment as well as a style icon. Her known moral transgressions add to her aura and dazzle. Accused of fascist sympathies and Nazi friends, she is an object of fascination that has increased with the years.

Wallis Simpson was guilty of four things: she was a woman, she was a commoner, she was a double-divorcee and she was an American. But, notwithstanding all these handicaps, she still managed to storm the House of Windsor. She shook the fusty old English establishment and she got her man, even when the man happened to be a king! The surprise here is even greater because there was something manly about this femme fatale.

In 1936 Edward VIII, who recently succeeded his father George V, made it plain to the English establishment, politicians and churchmen alike, that he intended to marry this double divorcee, his long-standing mistress, an unprecedented move. Oh, no, you are not, came the response, not if you want to remain as king. Oh, yes, I am, and I don't want to be king. Wallis and love came before throne and duty. Edward abdicated and, as Duke of Windsor, married his Duchess. They were such an odd couple, the handsome and debonair prince and the gauche, angular and rather masculine Wallis. Look at her picture. Shes not just conventionally plain; shes positively ugly. But what she lacked in looks she made up for in wit and personality. She also made up for it with other talents, at least according to long-standing rumours, talents acquired in some of the less salubrious fleshpots of old Shanghai. But there is, she goes on to say, a far deeper and darker secret, something that would account for her appearance and her personality. The suggestion is that she might have suffered from a condition now referred to as Disorder of Sexual Development (DSD) or intersexuality, something that apparently affects 4000 babies each year in the United Kingdom alone. I can only describe this as nature not making up its mind, producing a child that is not quite one thing and not quite the other.

Its also possible, the author further suggests, that Wallis was born as a pseudo-hermaphrodite, with the internal reproductive organs of one sex and the external organs of another. This is a matter incapable of any proof but apparently, and amazingly, although she was married twice before she met Edward she once told a friend that she had never had sexual intercourse with either of her husbands, refusing to allow anyone to touch her below what she referred to as her personal Mason-Dixon line.

Writing in 1958 the biographer James Pope-Hennessy said that she was one of the very oddest women that he had ever seen She is flat and angular and could have been designed for a medieval playing card. I should be tempted to classify her as an American woman par excellence were it not for the suspicion that she is not a woman at all.