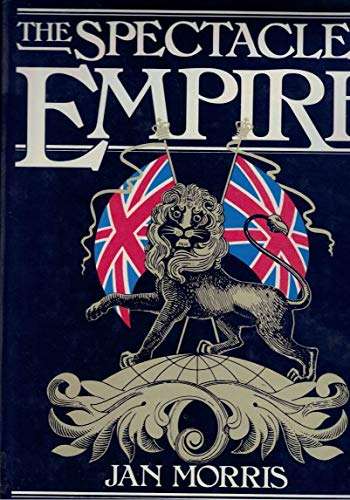

Published by Faber and Faber, 1982, hardcover, illustrated, some rippling to lower RH corners of pages not affecting text or illustrations, otherwise condition: very good.

The British Empire was one of the most astonishing phenomena of modern history: a quarter of the earth's landmass (almost 11 million square miles) under the suzerainty of a small island off the Atlantic coast of Europe. The empire has been acquired almost by accident, an island here, a port there, but by the end of the nineteenth century it dominated the lives of over 372 million people. The English language, British ideals, British notions of justice and civilization, British taste in art and architecture could be found in every corner of the world, in Europe, Africa, America, Asia, Australasia and on what the Colonial Office list as 'nearly all the isolated islands and rocks in the ocean'.

Jan Morris is one of my favourite writers about people and place. She was interested in everything that gave places their character their geography, their history and culture and, of course, their people. And her books are richly rewarding as a result, having none of the sense of superiority or condescension that so many so-called 'travel writers' employ to amuse their readers. Yet she is often acutely funny.

The book is really a collection of essays, copiously illustrated with photographs from the late nineteenth century when the British empire, the largest empire in history, achieved a kind of fulfilment: not just of political, historical or economic ambition, but of spectacle and style. She says that its impressionistic, not detailed, but as she wrote it very soon after finishing her great , you can be confident that both the generalisations and specifics are on target. Here she concentrated on the spectacle of Empire, expressions of unbounded self-confidence and sense of superiority at all levels social, political and economical. Flags, uniforms, parades, swagger, complacency were always part of the imperial presence and became increasingly significant under the portly Queen Victoria, whose Diamond Jubilee coincided almost exactly with the peak of imperial glory.

Ostentation and braggadocio were at first a protective device in the Americas or India, she says the grander you were and the more important you appeared to be, the safer you were likely to be. Over the years, it had become a maxim of British imperial method that ostentatious effect was not only necessary to survival, but essential to domination too, provided it was supported by power.