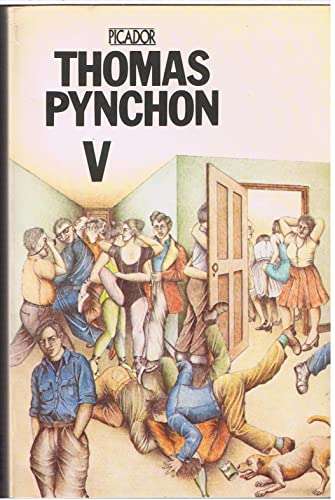

This is the first novel by the author of Gravity's Rainbow, and a profoundly impressive and original work in its own right. The search for the mysterious V ranges from New York to Cairo to Alexandria to Malta. Apart from its strange heroine, the book's characters include sailors, spies, priests, philosophers, bums ands bawds.

Having just been released from the Navy, Benny Profane is content to lead a slothful existence with his friends, where the only real ambition is to perfect the art of "schlemihlhood," or being a dupe, and where "responsibility" is a dirty word. Among his pals--called the Whole Sick Crew--is Slab, an artist who can't seem to paint anything other than cheese danishes. But Profane's life changes dramatically when he befriends Stencil, an active ambitious young man with an intriguing mission--to find out the identity of a woman named V., who knew Stencil's father during the war, but who suddenly and mysteriously disappeared.

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr. is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, genres and themes, including history, music, science, and mathematics. For Gravity's Rainbow, Pynchon won the 1973 U.S. National Book Award for Fiction.

Hailing from Long Island, Pynchon served two years in the United States Navy and earned an English degree from Cornell University. After publishing several short stories in the late 1950s and early 1960s, he began composing the novels for which he is best known: V. (1963), The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), and Gravity's Rainbow (1973). Rumors of a historical novel about Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon had circulated as early as the 1980s; the novel, Mason & Dixon, was published in 1997 to critical acclaim. His 2009 novel Inherent Vice was adapted into a feature film by Paul Thomas Anderson in 2014. Pynchon is notoriously reclusive from the media; few photographs of him have been published, and rumors about his location and identity have circulated since the 1960s.

"V" isn't so much a difficult novel to read - it is after all just words, most of which are familiar - as one in which it is sometimes hard to understand what is going on and why. What does it mean? Does it have to mean anything? How does it all connect?

Ironically, if not intentionally, the inability to determine what and why, as well as who, is part of its design. Pynchon mightn't want to answer all the questions he or life asks. However, that doesn't mean there isn't a lot of food for thought in the novel.

Pynchon actually tells us a lot all of the time. Like "Ulysses", there are lots of hints and clues and allusions, and it's easy to miss them, if you're not paying attention to the flow of the novel and taking it all in. It's definitely a work that benefits from multiple readings.